Zones of Proximal Development

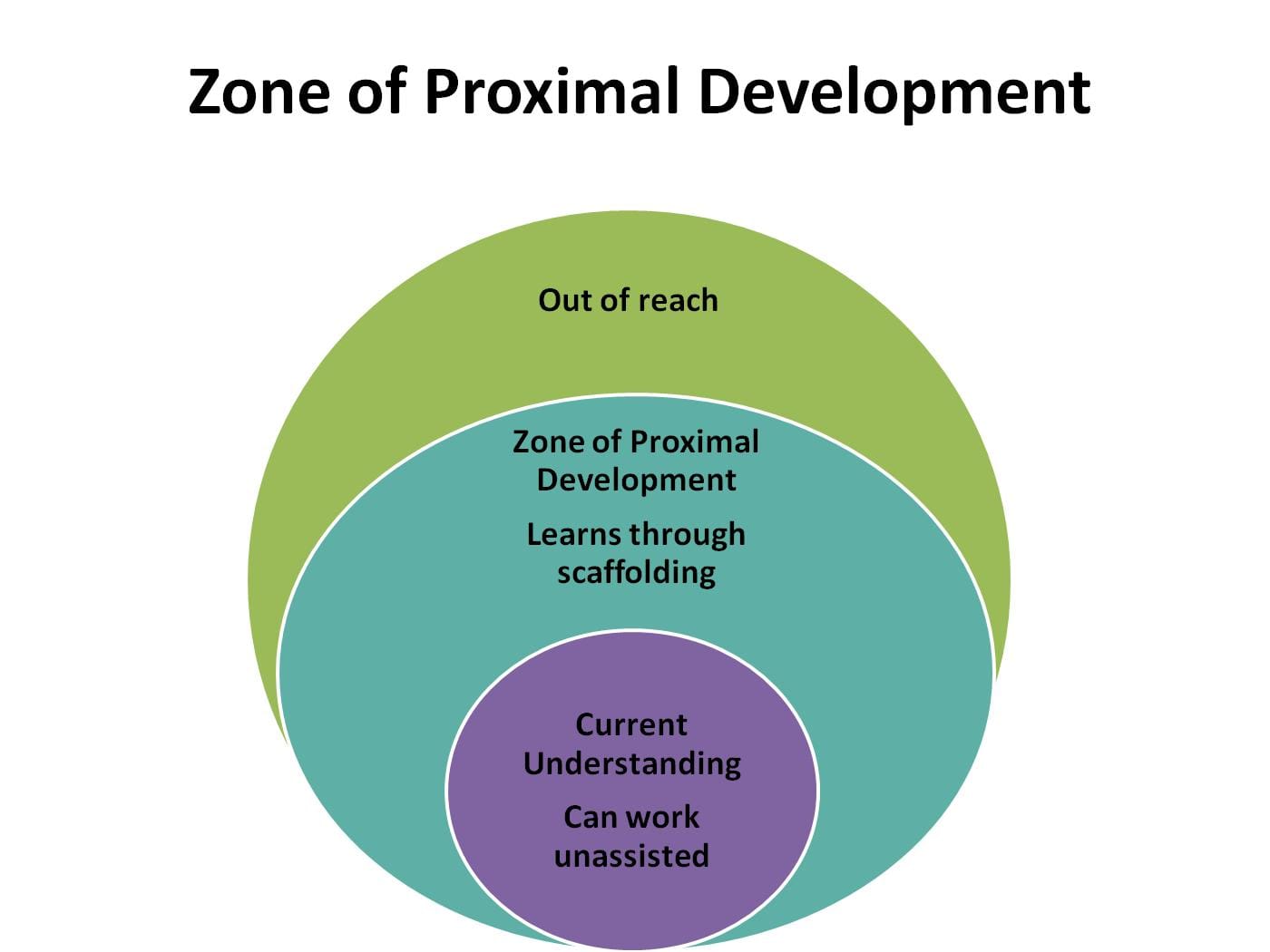

The roots of Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) go all the way back to the the work of the philosopher of language and psychologist, Lev Vygotsky. One of Vygotsky's core ideas was that of the Zone of Proximal Development, or "ZoPeD." According to Vygotsky, the ZoPeD was the developmental "sweet spot" where learning could occur. Consider teaching your child to ride a bike. If your child already knows how to ride, there is no reason to try and teach them – they have moved beyond this particular ZoPeD. If your child is not capable of learning, for whatever reason(s), then it would be premature to try and teach them – they have not yet reached the lower limits of this particular ZoPeD. However, if they are developmentally ready to learn, again for whatever reason(s), then they have reached the ZoPeD for this skill, and you as an adult can scaffold your child's emerging skill as they move through the corresponding ZoPeD.

One of Yrjö Engeström's contributions to the historical development of CHAT itself, is expanding the notion of a ZoPeD, from a focus on a single individual (which was Vygotsky's original emphasis), to a focus on a group of individuals, or an activity system (see my post, Activity Systems). According to Engeström, activity systems navigate ZoPeDs, just as individual humans do. In the dairy farm example, discussed in my first few posts, Earl Spencer (including his family and his cows) was moving through a ZoPeD as he transitioned from a traditional, "industrial" mode of farming to a nontraditional, "organic" mode of farming. Based on Wendell Berry's account of this transition – in the essay "Solving for Pattern" – it does not sound like there was anyone actively scaffolding Earl Spencer's development as a dairy farmer, but that doesn't mean there wasn't scaffolding in place. You may recall, from my earlier post – Earl Spencer's Farm – that Berry introduced his discussion of the farm as follows:

It would be next to useless, of course, to talk about the possibility of good solutions if none existed in proof and in practice. A part of our work at The New Farm has been to locate and understand those farmers whose work is competently responsive to the requirements of health. Representative of these farmers, and among them remarkable for the thoroughness of his intelligence, is Earl F. Spencer, who has a 250-acre dairy farm near Palatine Bride, New York.

This quotation suggests that, at least in part through the work of The New Farm, that these ideas were "in the wind" during the time that Earl Spencer was transforming his dairy farm (activity system). One more example is Wendell Berry's essay, "Think Little," which was first published in 1970, ten years before "Solving for Pattern" was first published. "Think Little" already contained most of the ideas present in "Solving for Pattern," albeit in a less generalizable form. What these examples indicate is that there was a cultural and social context in place, that at least in principle could scaffold Earl Spencer's journey through his farm's ZoPeD. We cannot determine, based on Berry's essay, specifically which ideas Earl Spencer had been exposed to, but it seems likely that he was aware of at least some of these developments.

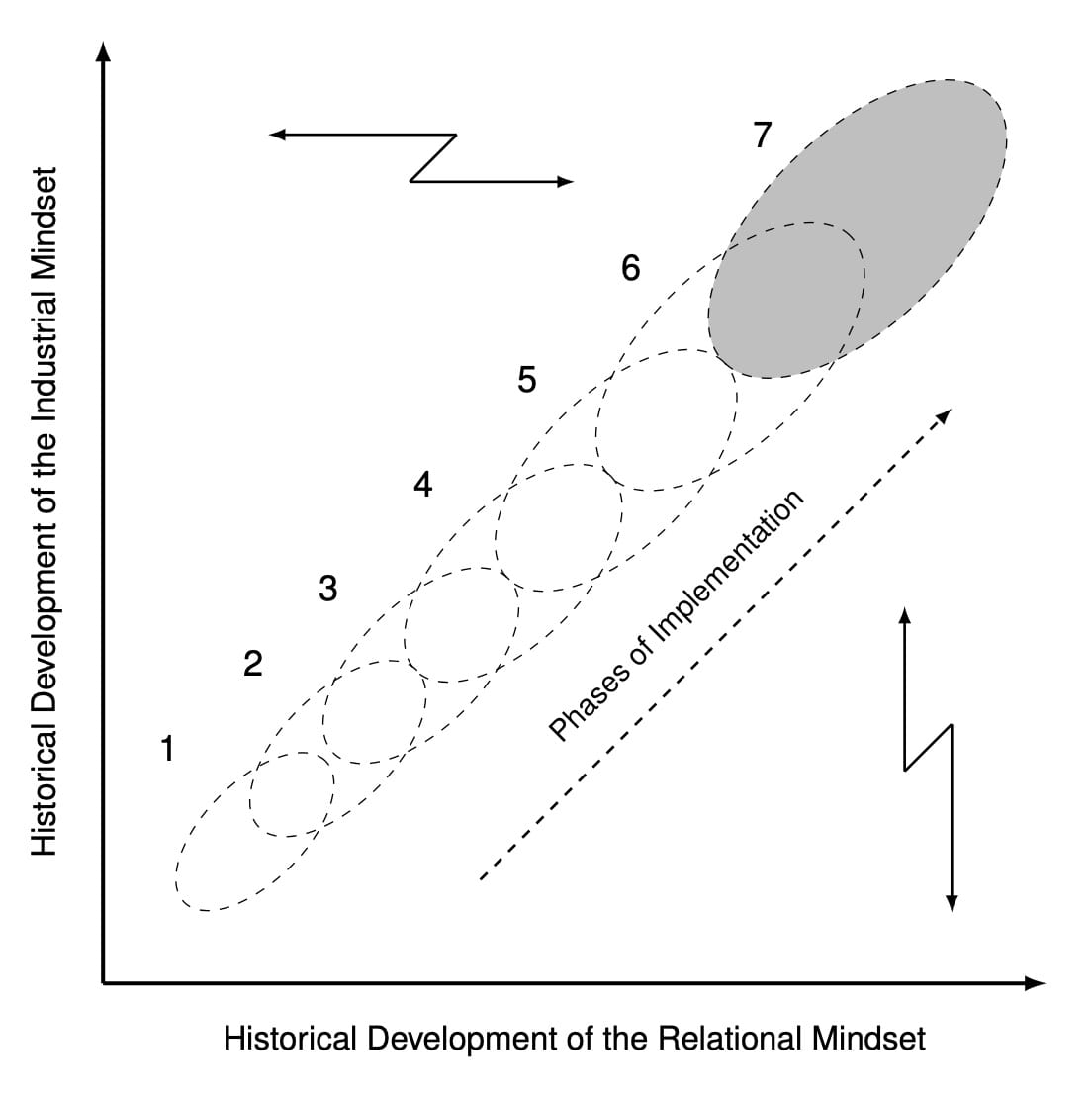

The first diagram on this page shows the ZoPeD, as it applies to supporting the development of a single human (by the way, Michael Tomasello's book, Becoming Human: A Theory of Ontogeny, is excellent, and presents a "Neo-Vygotskyian" theory of human development). The second diagram shows the organizational ZoPeD, as conceived within the context of program implementation or system change. The second diagram has three main aspects:

- The ZoPeD itself, which applies to an activity system that is in undergoing some kind of transformational process, such as Earl Spencer's efforts to transform his dairy farm. What's shown in this diagram is a series of ZoPeDs, which reflects the fact that as the activity system changes over time, so will its capabilities, challenges, and goals. Each ZoPeD in this series has associated with it a particular cycle of expansive learning, which is implicit, and reflects (ideally) a process of solving for pattern.

- Second, there are the two axes of the diagram: One of these axes reflects the "Historical Development of the Industrial Mindset," whereas the other reflects the "Historical Development of the Relational Mindset." Berry mentions both mindsets in his essay, for example when discussing Standards for Good Solutions (#5), where he says, "A farm that has found correct agricultural solutions to its problems will be fertile, productive, healthful, conservative, beautiful, pleasant to live on. This standard obviously must be qualified to the extent that the pattern of the life of a farm will be adversely affected by distortions in any of the larger patterns that contain it. It is hard, for instance, for the economy of a farm to maintain its health in a national industrial economy in which farm earnings are apt to be low and expenses high." In other words, farmers (and everyone else) must balance the demands (or pulls) of both mindsets. Now, when I say "Historical Development of ...," what I mean is that these mindsets change over time. For example, the Industrial Mindset is being transformed today by the onset of artificial intelligence; the Relational (Organic) Mindset is being transformed by the impact of the internet and climate change. I will have (much) more to say about these two mindsets in subsequent posts.

- Third, there are the two jagged arrows in the diagram, each one connecting the ZoPeDs to one of the two axes. These reflect what Yrjö Engeström considers the fundamental contradiction of any activity system, at least as they arise in capitalist societies. The Industrial Mindset emphasizes profit, efficiency, centralized control, and immediate returns. In contrast, the Relational Mindset emphasizes health, effectiveness, localized control, and a certain slowness. Anyone trying to make a living in the US today will inevitably experience and be stretched by this contradiction. One well-known example from the CHAT literature is that of a person who wants to practice as a doctor: They will be tested by a system that requires they earn enough to pay the bills, which in many ways interferes with their ability to serve their patients.

Remember, first, that these posts form a series, just like chapters in a book; this is especially true of this core series of posts, focusing on Wendell Berry's "Solving for Pattern." The next post will be last one focusing specifically on "Solving for Pattern," after that I will begin branching out into examples and elaborations of these core ideas. And remember, second, that you can ask me questions by sending me an email (d.cross@tcu.edu); I would like on occasion to devote a post just to answering or responding to questions. (I have noticed in the ghost forums, that several users have asked for the ability to include comments, but ghost doesn't have that ability yet.)_