The WilCo Story Illustrates the TBRI Practice Principles - Part 1

Let me begin by apologizing for taking so long to get this post published ... I really have no good excuse, but the last two months have been challenging, in a number of different ways. Some challenges were positive (finishing our book, preparing for the holidays), whereas others were negative (illness, national politics). Now, I am ready to move on. In this post I continue with "The WilCo Story," which I started in the previous post, and which is based on the fourth of my "Solving for Pattern" essays. Since some who read this post may not be familiar with the TBRI Practice Principles, my next blog post will focus on those.

There are seven TBRI® Practice Principles, and I will deploy them as a way to highlight certain features of the “The WilCo Story.” In the first “Solving for Pattern” essay, I referred to them as the TBRI® “Implementation Principles,” but we have since started referring to them as the TBRI® Practice Principles. The reason for this change is significant: “Implementation” implies that there is a “thing” to be implemented, more or less as is, whereas in actual fact TBRI®“implementation” is a matter of KPICD staff and partners co-creating a trauma-informed practice, based on TBRI® Principles and Strategies, through a dynamic and open-ended process of expansive learning. In order to keep the length of each blog post manageable, I will feature the first four Practice Principles in Part 1, and the last three Practice Principles in Part 2.

Trust-Based and Relational

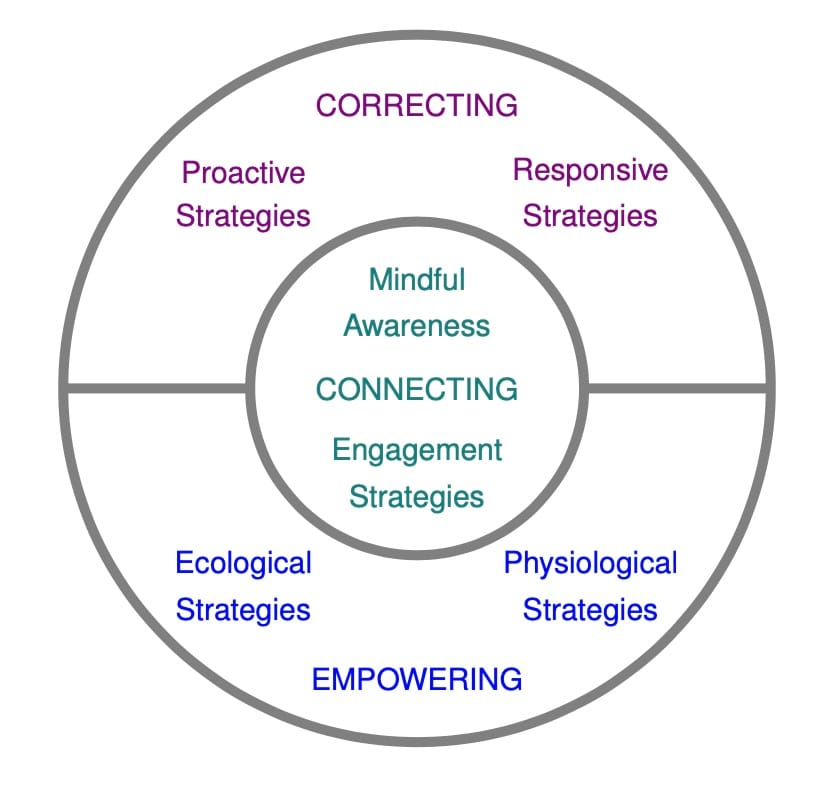

There are two senses of this principle that seem to be important to the construction of a valid and robust TBRI® practice. The first is relatively straightforward: The practice of TBRI® should be founded on the TBRI® Principles and Strategies, summarized in Figure 1. In other words, if your intention is to create a trauma-informed culture of care and practice using TBRI®, then you should in fact put into practice the TBRI® Principles and Strategies — TBRI® should form the core of your work. It is clear from the TBRI® Implementation Timeline and the TBRI® Implementation Strategies, as well as from our own observations and the rich set of TBRI-based artifacts produced by the WCJS staff, that TBRI® has in fact been implemented at WCJS.

Figure 1. Trust-Based Relational Intervention® (TBRI®) can be divided into three sets of principles: The Connecting Principles are grounded in attachment theory, and include Mindful Awareness and the Engagement Strategies. The Empowering Principles help provide a stable platform for Connecting and Correcting, and include the Ecological Strategies and the Physiological Strategies. The CorrectingPrinciples are designed to help adults shape behaviors and skills, and include the Proactive Strategies and the Responsive Strategies. TBRI is effective because these principles and strategies impact the child synergistically and holistically to promote healing, learning, and well-being.

The second sense in which “Trust-Based and Relational” is necessary for the construction of a valid and robust TBRI® practice is not as obvious as the first, but is equally important. The basic idea is simple: We need to not only “TBRI” the children or youth we serve, but also each other, and ourselves. In particular, leadership cannot expect staff to do the hard work of practicing TBRI® “on the floor” with youth, if leaders are not practicing TBRI® with the staff, and the staff are not practicing TBRI® with each other. As far as WCJS is concerned, I believe that the leadership created a organizational culture based on TBRI®, in both senses being discussed here, and can share an example which illustrates the point:

Once the initial round of training had been carried out, where each staff member had participated in at least one large-group training session, the implementation team came up with a highly effective sequel to the standard training format. Trainers, including administrative and counseling staff, began organizing brief, small-group sessions to focus more intently on specific aspects of TBRI® (e.g., The IDEAL Response©). Initially, the topics for these small-group sessions were chosen by the trainers, based on live observations and/or videotaped recordings. These small-group sessions afforded opportunities for discussion, questioning, and role play, in a setting that afforded greater psychological safety than the large-group training sessions. Once the staff became comfortable with this small-group format, their questions began to drive the topics and discussion. Notice that these small-group sessions – which could be labeled "Needs-based, Micro-dose, Small-group Conversations" – were both Trust-based and Relational. (I would like to thank Amanda Brunson who helped me enrich and validate my memories of these small-group sessions.)

Trauma-Informed

Since TBRI® itself is trauma-informed, any culture of care and practice that has integrity with TBRI® and the KPICD, will necessarily be trauma-informed. That said, Matt Smith and his staff took have taken their practice a step further, by integrating a cluster of trauma-informed programs, that are complementary and synergistic. These include Howard Bath’s “Three Pillars of Traumawise Care” and the Search Institute’s developmental programs (www.search-institute.org). Further, WCJS has integrated information and testing about ACEs into their training and programs, thereby elevating awareness and understanding of the prevalence and impact of relational trauma in the youth they serve. A few statistics are relevant to the purposes of this essay:

- 82% of residential youth have four or more ACEs (in the original ACEs studies, 16% of the sample had four or more ACEs);

- 98% of residential youth have at least one mental health diagnosis;

- 83% of residential youth have had at least some contact with CPS;

- 29% of residential youth were charged with assault, 23% for substance-related behaviors, and 19% for criminal activity (e.g., theft).

It is interesting (and, perhaps, important) to note that prior to the ACEs studies, the above information would have been presented without the ACEs scores — it seems much easier, at least to me, to label a youth a “bad kid” in absence of the ACEs scores, than it does when we have this information available. In any case, the above statistics make it clear that the need is great.

Humility and Grit

The seven Practice Principles were originally developed with KPICD staff in mind, but it has become clear to us that these principles apply to our partners as well. “Humility and Grit” are apparent in both the TBRI® Implementation Timeline and the TBRI® Implementation Strategies, listed above. Grit is evident from the degree of persistence required to stick with implementation for nearly four years now; humility is evident from the collaborative spirit that Matt and his team have adopted, working not only with KPICD staff, but with a number of other agencies and partners.

It's a Journey

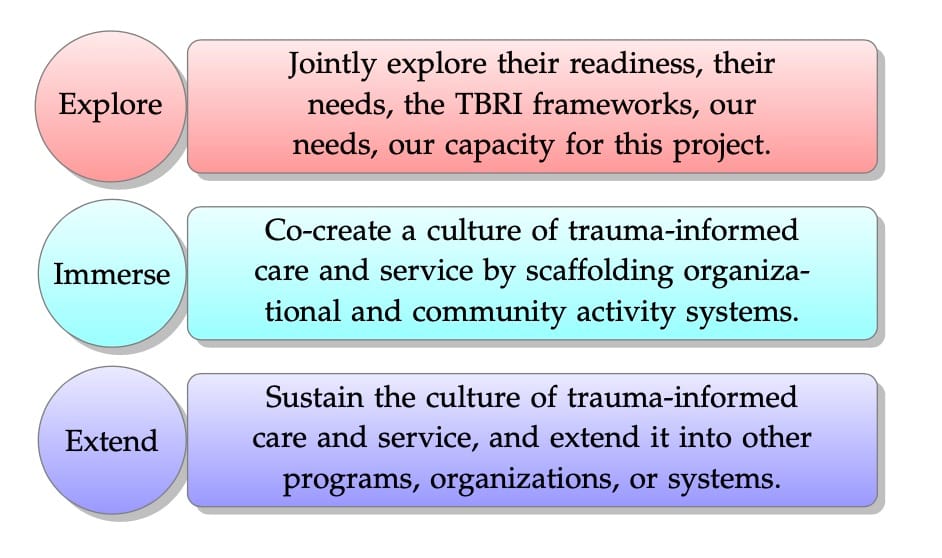

One of the most striking features of “The WilCo Story” is how well it illustrates the three-phase implementation framework shown in Figure 2, and discussed more thoroughly in the current version of Practitioner Training. Here is a quick breakdown of the three phases, as they apply to WCJS:

Exploration The exploration phase actually began prior to 2016, which is where the TBRI® Implementation Timeline begins: In 2010, WCJS began working with the Search Institute programs (Developmental Assets, Sparks, Developmental Relationships), and in 2014 began working with a variety of trauma-informed programs, including Equine Assisted Psychotherapy, Cinema Therapy, and the “Paper Tigers” and Resilience programs.

Immersion The immersion phase began in Summer of 2016, and we can follow its progress in the TBRI® Implementation Timeline and TBRI® Implementation Strategies; important milestones occurred in Summer of 2017, when WCJS Practitioners first held their own in-house training, and WCJS staff reframed the JSOs and JPOs as “Youth Engagement Specialists.”

Extension The extension phase began in November of 2017, when WCJS partnered with county judges in offering a one-day TBRI® Overview as part of the Behavioral Health in the Legal & Justice Systems Conference; as can be seen from the listing in TBRI® Training and Consulting, above, WCJS is now actively engaged in extending the reach of TBRI® into a variety of juvenile justice settings.

Figure 2. TBRI implementation typically occurs in three phases. During the first phase, exploration, we address issues such as organizational readiness, our ability to meet the organization’s needs, their ability to meet our needs, and informing them about the frameworks described in this blog post. During the second phase, immersion, we co-create with the organization (or community) a culture of trauma-informed care and service through training and consultation, by scaffolding their activity system through the Zone of Proximal Development (individually and organizationally). During the third phase, extension, the partner organization or community sustains and grows the culture of trauma-informed care and service, perhaps by extending it into other programs, other organizations, or other systems of care and service.