Activity Systems

Thus far in this blog there have been five posts:

Introduction. I introduced who I am, what I intend to do, why I am doing it, and how I will do it.

Bad Solutions. I introduced the article that inspired this blog – "Solving for Pattern" by Wendell Berry – and summarized the first topic: Two types of bad solutions.

Good Solutions. Here I summarize Wendell Berry's perspectives on good solutions – solutions that promote system health through solving for pattern.

Earl Spencer's Farm. Wendell Berry offers Earl Spencer's dairy farm as an example of a good solution.

Standards for Good Solutions. I share and analyze seven of the fourteen standards that Berry suggests.

Importantly, you (the reader) should realize that this blog is designed so that each new post builds on the previous posts, just like each chapter in a book builds on the previous chapters. Note also that you can access all of the posts on the website where this blog lives: solving-for-pattern.ghost.io; once on the website, you can move between posts using the "Previous Issue" and "Next Issue" buttons at the bottom of the post. (At this point in time, the "Browse All Issues" button doesn't seem to work, which is something I am trying to fix.)

Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT)

In the next three posts, including this one, I will be introducing you to CHAT, which has turned out to be a useful framework for implementing system change (by solving for pattern). I will lean heavily on the work of Yrjö Engeström, especially in regards to his two books:

- Learning by Expanding: An Activity-Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Studies in Expansive Learning: Learning What Is Not Yet There. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

One way to view CHAT is that it adds flesh to the bare bones laid out in Wendell Berry's essay, "Solving for Pattern." One could say that whereas Wendell Berry's essay tells us where we need to go (viz., health), CHAT tells us how to get there. My introduction to CHAT will focus on three core concepts: Activity Systems, Cycles of Expansive Learning, and Zones of Proximal Development. I will be introducing these concepts using Earl Spencer's dairy farm as an example. In later posts, I will use the CHAT framework to investigate how other change agents solved for pattern.

Activity Systems

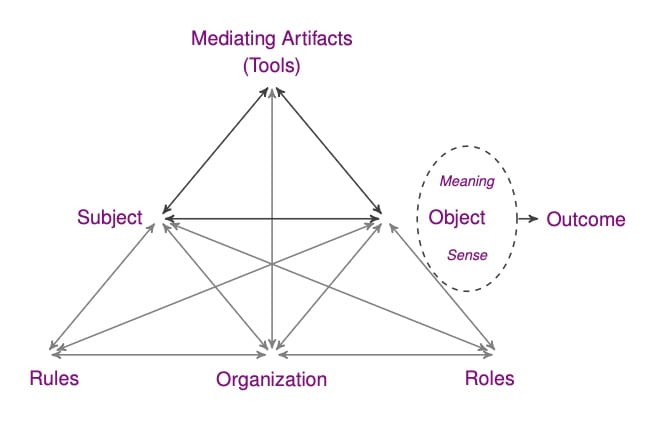

One of Yrjö Engeström's well-known triangle diagrams is shown in the figure above, which depicts the major elements of an activity system. The arrows linking, say, Subject and Rules, indicate that each element of the activity system is connected to each of the remaining elements – in other words, they constitute a cohesive and dynamic system with interconnected parts. Activity systems can be found in classrooms, workplaces, schools, sports teams, churches, military units, etc.

Subject

Earl Spencer is the “Subject” of this activity system, and an important feature of this particular “Subject” is his capacity for expansive learning: As Berry puts it, “A part of our work at The New Farm has been to locate and understand those farmers whose work is competently responsive to the requirements of health. Representative of these farmers, and among them remarkable for the thoroughness of his intelligence, is Earl F. Spencer, who has a 250-acre dairy farm near Palatine Bride, New York.” As part our work at the KPICD, we have had the good fortune to work with a large number of "intelligent subjects," and you will have an opportunity to "meet" them in this blog.

Organization

The "Organization" in this case is Earl Spencer's dairy farm; other examples include classrooms, schools, workplaces, clubs, and churches. It should be clear from Wendell Berry’s description of a good solution that Earl Spencer’s dairy farm is not just a collection of land, buildings, and equipment, but that it is a biological and social entity, characterized by patterns of relationship between community, farmer (and family), cows, crops, and land.

Roles

Although Earl Spencer remains the same person, so to speak, as he transforms his farm from a "conventional" activity system to an "organic" activity system, his role changes. This will become more clear when I discuss the object of the activity system, below, but for now we can say it this way: On his "old" farm, Spencer was a farmer-technologist, whereas on his "new" farm, Spencer was a farmer-ecologist. This transformation of role parallels, for example, what we have seen at the KPICD in our work with juvenile justice facilities, such as Williamson County, where the floor staff went from being "Juvenile Safety Officers" to "Youth Engagement Specialists." Same persons, different roles — same facility, different activity systems. (It is important to note that this was their own invention, which is a good example of expansive learning.)

Tools

The tools used on Earl Spencer’s farm appear not to have changed (much), but his use of those tools changed dramatically: less fertilizer, less food concentrates, more manure (including building of a manure pit), less use of feed grain, more use of roughage, less involvement by veterinarians, less wear and tear on equipment. These changes in tool use reflected changes in the object of the activity system, and the corresponding changes in rules. These transformations in tool use also parallel what we often see in residential programs that implement TBRI – for example, transformation of a restraint and seclusion room into a calming and sensory room.

Rules

The rules changed significantly: (a) a smaller, more productive herd; (b) phasing out the use of purchased fertilizers; (c) phasing in the use of manure, produced on the farm itself; (d) better husbandry of cropland, more frequent rotation, better timing; (e) gradual reduction of grain in the feed rotation, and concurrent increase of roughage; (f) a breeding program which selects for more efficient roughage conversion. All of this was designed to bring the farm into better balance, to restore healthy patterns within the activity system. Once again, we can see parallels with our own work at the KPICD: To take but one example, in school settings where TBRI is being implemented we typically see an emphasis on solving problems in the classroom, in the moment, as opposed to sending children to the principal’s office, or suspending them from school.

Object

The most important feature of any activity system is its object, which is the (collective) psychological entity that gives purpose and meaning to the activity (in this example, dairy farming). The object provides a framework for making sense out of all the activity system components, including the individual actions of the persons (subjects) who participate in the activity system. In the Earl Spencer example, the object was transformed from one that reflected the “industrial” mind, to one that reflected the "ecological" or "organic" mind. It is the object that gives meaning to all of the changes occurring within the activity system, including changes in roles, tools, and rules. Object are complex entities, and in later on I will be devoting at least one post just to this important concept.

Contradictions

Implicit in the activity system diagram are the inner contradictions that can drive change in activity systems. This is a complex topic, and I will return to it again and again in this "Solving for Pattern" blog. For now, I will focus on what activity theorists consider to be the primary contradiction, namely, the contradiction between the use value and the exchange value of a product or service. The easiest way to see this for the farm example is to focus on the cows themselves. From the standpoint of the "industrial mind," the exchange value of the cows is dominant: After all, the purpose of dairy cows (from this perspective) is to produce milk that can be sold on the market. From this perspective, cows are simply milk-producing machinery, that are part of a milk-producing factory. Cows are mere cogs in the wheels of industry. From the stand point of the "ecological mind," or the "organic mind," the use value of the cows is dominant: The cows are part of an ecosystem (activity system) that not only produces wealth (profit), but also produces health (e.g., the cows’ manure is used to fertilize the crops). And this represents not only a moral good, but a utilitarian good: Healthy farms are sustainable, and they are sustainable because of the intrinsic patterns that maintain the overall health of the farm. Examples from our own work at the KPICD that illustrate the fundamental contradiction, are the — perhaps apocryphal — stories about families that "warehouse" foster kids, solely for their exchange value, which is the per child payout from the State. In these tragic instances, the foster children’s use value, based on caregiving that is trust-based and relational, is minimized, or neglected altogether.

Outcomes

An important feature of CHAT is that outcomes of the activity system are seen as "products" of the object – if you want to understand why you are getting certain outcomes, then you need to understand the object that is giving rise to those outcomes. In the case of Earl Spencer's dairy farm, when the object changed – from an industrial mindset to an organic mindset – the outcomes changed: profit margins improved, but more importantly for the long-term life of the farm (and farmer), the health of the farm itself improved. In other words, the object drives the activity system, including its associated outcomes.

In the next blog post I will discuss Cycles of Expansive Learning, again using Earl Spencer's farm as an example. If you would like to learn more about Wendell Berry, there is a good article in The New Yorker: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-new-yorker-interview/going-home-with-wendell-berry